So I watched Gladiator 2. [Caveat lector: lots of spoilers ahead]

And it was a lot of things - thrilling, epic, impressive in its sheer scale as well as its diligent attention to historical detail.

It was, undeniably, a Ridley Scott production— in that, it was full of disposable, underwritten women who either die in the service of manpain (Arishat) or who exist as mother/wife/daughter, powerful primarily by their relationships with powerful men…. and then die in the service of manpain (Lucilla). Delayed gratification— what privilege!

But okay, okay— I’ll level with you. It wasn’t all bad. It was mostly good! But I just needed to get that off my chest.

In spite of my feminist fit of pique— I actually really did enjoy myself a lot because I love classical reception. There is no cooler feeling than seeing all of the stories and moments from the lives of people you’ve studied for so long in a very clinical way— through scholarly text and translated Latin— brought vividly to life.

All reception of Classics brings new and fascinating dimensions to ancient stories, by virtue of the medium into which the story or image from antiquity is translated. Books are incredible at building out worlds and languages and philosophy (currently reading The Will of the Many by James Islington and it’s actually a perfect book). I love ancient art re-imagined in modern illustration styles and graphic design (like the iconic flahroh), too.

But cinema is in some ways the ultimate medium. Movies are such a potent method of storytelling because they’re so many art forms combined! Cinematography, sound design and score, writing, performing, costume and set design— I’m just naming Oscars categories right now, which, by the way, I only recently learned the original Gladiator won one.

It’s almost embarrassing to admit that I only just watched it now. After I watched 2. All that about the power of cinema and I blaspheme!

Regardless — we’re not talking about the original Gladiator right now, though I could write a whole diatribe on that later — this post was inspired by its sequel, which while I watched in gargantuan IMAX, I noticed I couldn’t help but keep noticing things!

I noticed historical things that I remembered actually happened or happened some other way than the movie chose to depict. I noticed choices Ridley Scott made in his depictions of things I’d seen described in textbooks. I noticed literary references that leant so much more meaning to the moments in the movie when I remembered the context in which they were written.

Essentially I am using my classics degree because it has greatly enhanced my moviegoing experience in this one instance—providing, in my head, a running commentary of sorts— which I have refined and collected for you below in, as the great Jenny Nicholson says, an internet-friendly numbered list.

So without further ado, Gladiator 2, annotated:

1 ) After Numidia is conquered, we see all the conquered people sitting around the burning bodies, crying and throwing their hands in the air.

I was impressed to see this fairly accurate depiction of ancient mourning rituals.

We know from textual evidence, primarily literary and artistic, that mourners would scream, cry, tear their hear out, beat at their breasts, writhe around in ashes. They would make vocalizations with their mouths called ululations.

In the movie, what I took umbrage with was the fact that Hanno (Paul Mescal) and the Numidian king, Jugurtha (Peter Mensah) do not cry and ululate.

This felt like reading modern expectations of masculinity into Ancient people who did not subscribe to such social standard.

Achilles, Odysseus, Aeneas, Heracles, you name it— all of these men, held up paragons of masculinity in their time and now, textually cry and freak out and ululate. It was just part of their natural, cultural response. Sure some rituals and ululations were unique to women, but men seriously cried, and emotion itself is a part of being a human and not an indicator of weakness.

It’s just an adaptational choice I don’t agree with because I feel like it portrays this arbitrary ideal of masculinity in direct contradiction with the interesting historical attitude which if the opportunity was seized would showcase an alternate, healthy ideal of masculinity where men can display emotions and it’s okay!

Citations:

Garland, Robert. The Greek Way of Death. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Monsacré, Hélène. 2018. The Tears of Achilles. Trans. Nicholas J. Snead. Introduction by Richard P. Martin. Hellenic Studies Series 75. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. **http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_MonsacreH.The_Tears_of_Achilles.2018**.

2) Acasius’s triumphal procession.

Even though Pedro Pascal’s character Acasius was not a real historical figure, his parade through Rome in a horse-drawn chariot was a representation of something that really happened!

Triumphal processions were a way to show off spolia, all the things AND PEOPLE looted from the conquered lands. There would be elaborate costuming, horse-drawn chariots, and general raucousness throughout Rome.

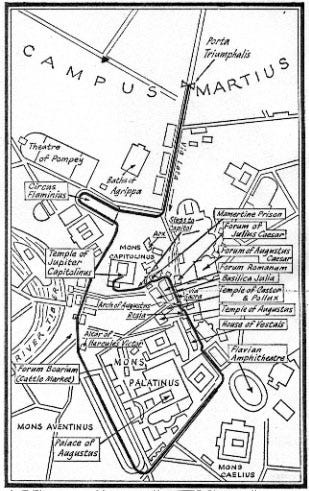

Josephus famously writes about the triumphal path— how it wound through the city, and people would clamber for spots, and their were known stops and signposts and a carefully organized route that would take the victor through the most iconic spots in Rome, ending at the Capitoline where the Imperial Palace was.

Fun fact about triumphs— there was this super weird, possibly apocryphal, story that during the triumph, when the triumphator — guy getting honoured — would go to get crowned with laurels, an enslaved person would whisper “Memento mori” into their ear so they didn’t get too big of a head.

There are a lot of ancient sources that talk about this but they may have been exaggerating or repeating myths since a lot of them were writing about triumphs long after they were no longer happening (at least not in the same way).

Citations:

Josephus, trans. Whiston: https://avande1.sites.luc.edu/jerusalem/sources/titus-triumphal-procession.htm

Beard, Mary. The Roman Triumph. Harvard University Press, 2007. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vw5.

3 ) Flooding the Coliseum for a naval battle (naumachia).

I enjoyed this immensely, not only because it was an exciting sequence, but also because these really happened in Ancient Rome!

Flooding the Arena to re-create famous naval battles was a form of gladiatorial combat called “Naumachia” or ναυμαχία which means “Boat Fight”

How did they get the water in there? Well, there was a series of tunnels underneath the Coliseum which were connected to the Roman aqueducts. These tunnels were also used for ferrying the humans and animals that would fight in the coliseum, but if they were cleared out they made perfect channels for both flooding the arena and later draining it.

A moment for the aqueducts—

They carried tons of water throughout the city which helped not only irrigation but also powered the many baths in the city— which were a huge part of Roman culture, hygiene, and social life.

Senators and emperors from the beginning of the republic into the empire gained a lot by investing in public works. They could put their names on these giant, important pieces of urban infrastructure and cement their family’s legacy.

Citation:

Herodotus. “The Epic Galley Battle of the Ancient Sea.” In The Ocean Reader: History, Culture, Politics, edited by Eric Paul Roorda, 205–9. Duke University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smqbv.49.

Ted Ed video for illustration:

4 ) When they complained that Rome smells really bad.

Just for your own good don’t look up things about Roman latrines and things just close your eyes and think about how they did have baths. They did bathe regularly. I have to believe they did. Even if they washed their clothes with pee— realistically, where else would they have gotten all that ammonia?

5 ) (Rich, Patrician) Women doing politics, plotting to overthrow the government!

Let’s take a moment for the icon, Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla, or as we know her, just Lucilla, played by Connie Nielsen.

Lucilla was a real historical figure— the second daughter of Marcus Aurelius and Empress Faustina the Younger! She was by all accounts a dutiful Roman noblewoman— she fulfilled her role by getting into a politically advantageous arranged marriage with Marcus Aurelius’s co-emperor Lucius Verus.

While she did not have any illegitimate children with gladiators (that we know of), she did attempt to throw a coup and get her little brother off the throne (as an older sibling, I can understand the impulse).

She was murdered by Commodus at age 33 in 182 BCE, so, sadly, she didn’t actually even live to see Caracalla and Geta on the throne. I like that the movie changed this! More women at the cost of historical accuracy? To me, the benefits outweigh the costs.

In many ways Lucilla was a girlboss, I think she could have been emperor if misogyny didn’t exist. In many ways the Hillary Clinton of her time… sorry if that offends you and you stan Lucilla or something— but let’s have a little perspective— both in the text of the movie and historically she was a slave owner.

And I am sorry but I can’t even talk about Arishat or I get mad. Just look up “women in refrigerators,” and join me in my perpetual exhaustion over female characters that are only written to be promptly disposed of so that their death can further male characters’ pain and story arcs.

To some degree, the way women are treated in this movie is to be expected in a big budget blockbuster action movie set in Ancient Rome, where women’s lives are known about little. Maybe I should give Scott credit for taking into account some of the more up-to-date information on for making the women in his story agents to some extent— warriors and pseudo-politicians — before their demise. Maybe.

Also I do want to acknowledge this news going around that Egyptian-Palestinian actress May Calamawy’s had a big role in this movie that got cut— although there’s not been any statements from her or Ridley Scott directly explaining why she was cut out of the movie or if it had anything to do with her being Palestinian — cynically, I wouldn’t be surprised, though I am disappointed. Even more cynically, I don’t think Ridley Scott needed an excuse to cut a woman from his movie. Regardless, I would have loved to see her in this, and, obviously, Free Palestine.

6 ) Now bear with me while I just get all of the Latin stuff off of my chest:

One thing that was interesting was the movie stylized the title like this: “GLADIIATOR” The actual plural of “gladiator” in Latin is “gladiatores” so as much as I wish it could be the case “GladiatorII” would not have worked. But, the plural of “gladius” (meaning sword), which is in the root of “gladiator” (one who bears a sword), is “gladii” even if it wasn’t on purpose— I’ll take it.

At one point in the movie, I think when the Praetorians are going to go bust Lucilla and the plot to overthrow the government, the Praetorians run past a a rare piece graffiti in actual Latin that says “Irrumabo Praetoriani” The graffiti means “I will fellate you Praetorians” which doesn’t really sound as effective in English— but it’s a reference to Catullus 16, a poem Catullus wrote to his frenemies Furius and Aurelius and which famously begins “Pedicabo et irrumabo vos.” Check out the full poem and its translation— it’s a fun Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catullus_16

The Aeneid verse that Paul Mescal quotes:

The gates of hell are open night and day;

Smooth the descent, and easy is the way:

But to return, and view the cheerful skies,

In this the task and mighty labor lies.

[Facilis descensus Averno: Noctes atque dies patet atri ianua Ditis; Sed revocare gradum superasque evadere ad auras, Hoc opus, hic labor est.]

The Aeneid, Book 6, l. 126ff (6.126-129) [The Sybil] (29-19 BC) [tr. Dryden (1697)]

This is from Book 6 of the Aeneid in which our hero Aeneas and crew FINALLY arrive in Italy after a long rip-off of the Odyssey’s Apologue, and go on to rip off the Odyssey’s katabasis.

Katabasis means a descent or “going down”, and it essentially denotes a common task for an epic hero— a journey into the underworld, from which, crucially, they must return. Katabasis as a concept is also paralleled in Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey— the entry into the unknown.

When Paul Mescal quotes these lines, he speaks the Sybil’s words of warning to Aeneas before the descent. In repeating these instructions to himself (and even more boldly, in front of the emperor), Hanno/Lucius indicates his clear-eyed awareness of where he is going, and what he is doing. Where once he was a free warrior in Numidia, by the time Mescal quotes this line, he’s descended— now he is a prisoner of war, and an enslaved gladiator in Rome. His body and life are owned by someone else who demands he subject himself to violence and physical abuse— he is socially dead, and in all aspects except physical, in the underworld.

Citations:

More detail on gladiators as slaves: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/gladiators.html

Patterson, Orlando. Slavery and Social Death. https://cominsitu.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/orlando-patterson-slavery-and-social-death_-a-comparative-study-1985.pdf

When Mescal later goes down into the secret inner part of the gladiator’s cells, where they illicitly hung up Russel Crowe’s armour from the last movie, it perfectly mirrors the journey Aeneas takes in Book 6 of the Aeneid, where he is literally reunited with his dead father who gives him strength and advice for the journey ahead. Without a hint of irony— good work here, Ridley Scott.

The Aeneid is is many ways considered the foundational text of Rome. It was a political project commissioned by Augustus through his talent scout Maecenas. So I was genuinely so excited to see it included— of course he would know the Aeneid, and it’s not even just the smoking gun of his Princess Diaries-esque secret heritage, but it’s delicious worldbuilding to accurately reflect a cultural reference that would be known to Romans.

Aeneid book 6: Harrison, E. L. “Metempsychosis in Aeneid Six.” The Classical Journal 73, no. 3 (1978): 193–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3296685.

I also really loved the touch where the movie shows us Lucilla had this verse painted on the walls of her home— this moment was actually quite accurate— it was common for elite households to have poetry and depictions of mythic events painted as murals on the walls.

Anyway— go read the Aeneid, it’s Homer fanfiction, but it’s good. Would bookmark on AO3.

I’m on record having enjoyed this translation: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/602340/the-aeneid-by-vergil-translated-by-shadi-bartsch/9781984854124

LAST LINGUISTIC NITPICK — At one point Macrinus says to Paul Mescal — “you have timos — that rage” Ooh— that’s not—

Timos means respect/fear

Menos is rage

μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ… he beginning of the Iliad goes “Sing to me goddess of the rage—”

It just grinds my gears because he compares Paul Mescal to Achilles like one line later, I just think he should have used the right word because it’s the most famous opening line in all of human literature okay, sue me!

7) OK now that that’s over— onto those freaky deaky emperors…

Perhaps the main question you’re asking when we see Caracalla and Geta was — were they really like that? With the monkey and everything? The answer is… no… yes… kinda… it’s complicated.

It’s not that this representation of their bumbling, corrupt, hedonistic style of conduct is totally off base. We don’t know that Caracalla and Geta were particularly effective in their positions, but as historians… we have to exercise a little more nuance. This movie arrives at this depiction of the two emperors by instrumentalizing prevailing historical impressions and manipulates the available incomplete and biased sources at face value to create the silver-screen worthy villains. It does this for good reason: it’s more fun. And there’s cinematic precedence for this exaggerated view of Roman “bad” emperors— Tinto Brass/Gore Vidal’s Caligula comes to mind!

But if you’re interested in comparing it to what really happened… you have to reckon with the assertion that I find harder to swallow than “they were kooky and corrupt”— and that is this idea that these idiots were the sole cause for the fall of the Roman Empire.

And I’ll tell you right away— no they weren’t. The “Empire” actually “fell” much “later”— I apologize for the heavy quotations but I once took a class where we spent an entire semester unpacking the idea of the fall of the Roman Empire and asking ourselves if it even did fall and if the Roman Empire is in the room with us right now. I’ll link some sources of some things we read if you’re curious about the real story, but it’s well out of the scope of this… which was once a movie review… and still may be yet. I think we can hold two truths in our heads— the movie was fun and the movie wasn’t historically accurate in some important ways. So let me attempt to provide you with a slightly more robust historical understanding and then we can go about comparing that to the artistic choices made in the film.

Further sources for the actual fall of Rome:

Burgess, R. W. The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization. Canadian Journal of History. Spring/Summer 2007, Vol. 42 Issue 1, p83-85. 3p

Collins, Roger. Early medieval Europe: 300-1000. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

With the black screen that greets us at the opening of this movie telling us it’s been so many years since Marcus Aurelius died and now… only just now… corruption is rife in Rome and the empire’s about to fall. Oh no!!

From this Ridley Scott sort of primes you to believe that everything was fine and then a bunch of terrible emperors showed up and ruined it for everyone— this really was not the case, and although I concede that it’s a serviceable political backdrop for your movie— it’s not a useful way of thinking about Rome.

Major caveat in this upcoming section— no Cinema Sins-ing is going on here. Ridley Scott ultimately wants to use Ancient Rome to tell a story about good versus evil, right? Evil emperors defeated by the super secret extra special lost grandson of “one of the good emperors of Rome.” But this is very much my personal gripe and vendetta but I sincerely believe that much like American Presidents, there were no good emperors of Rome.

I fully understand I am projecting my anachronistic human rights-based worldview onto the past and onto societies that didn’t necessarily subscribe to that kind of philosophy. I’m also aware that my point of view is particularly informed by the fact that I am a product of post-British colonialism. But with that disclaimer out of the way let’s just say it— occupying the position of emperor— a role purpose-built to uphold oligarchy, slavery, and violent dispossession in which you oversee the constant, brutal expansion of an empire through military invasion, disqualifies you from the running to be a good person. IN MY BOOKS, AT LEAST!

I want to destablize this idea— the easy political narrative of a before and after, which serves the purpose of the movie, but the actual truth of which is —in my opinion— just as interesting and worthy of discussion! And so, before we can get to Caracalla and Geta, let’s spend some time with “the before” where “everything was good” supposedly— “The Roman Dream.”

The empire technically starts with the fall of the republic at the hands of the one and only Julius Caesar (the Republic, by the way, was also not some secret good before times— it was a bureaucratically flailing oligarchy) and then starts in earnest with Augustus (Caesar’s nephew)— and then a bunch of stuff happens— colonial expansion, mostly— until we get to around 100 CE.

This is when we get into The Five “Good” Emperors (bear with me now — this part is eventually going to be relevant to Gladiator), they are as follows:

Nerva — the senate appoints him after Domitian is murdered, he’s good. Of course, in Roman Imperial terms, good just means he 1) conquered more lands, 2) built more buildings, and 3) gave people some modicum of social welfare.

Trajan — the Roman empire expands to the largest it’s ever going to get under Trajan in 117 CE when he dies. After this, expansion slows, stops, and even recedes in some places as other empires start taking their shit back. He was known for being good at war, giving to the poor, and I could tell you more, but I need to escape this rhyme. He also commissioned a really cool column.

Hadrian — hey fellas, is founding a hero-cult religion based in the city where your 19 year old lover died, and then renaming that city after him, and then subsequently spreading his image across your empire as the ultimate symbol of beauty… kinda gay?

Antoninus Pius - Pius means “pious” and is also the epithet used by Aeneas in the Aeneid. So he must have been good.

Marcus Aurelius - finally, a name I recognize! Paul Mescal’s grandfather! Author of the Meditations which has been chewed up and spit out by more Reddit atheists than its author could have ever nightmared… Marcus Aurelius was considered even in antiquity as a sort of “Philosopher king” because he had a lot of thoughts, I guess emperors before him didn’t really do that much. He continued the legacy of the past four emperors of consistently conquering, building, and giving some money/food to the people, and not having too big of an ego I guess.

(There’s also this guy Lucius Verus who was co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius but he never wrote a book that a thousand annoying philosophy majors became obsessed with so we’re not going to hear about him, also it’s the Five Good Emperors, Lucius get out of here)

And now… according to Ridley Scott… this is where it all goes wrong.

Commodus - the great failson. Depicted by Joaquin Phoenix in the first movie— or as Brian Cox would call him, wacky Whackeen— I’m going to assume if you’ve seen the first movie, you get the gist. Kind of a louche, spoiled kid who was not as effective as Marcus Aurelius. Because of that, and admittedly also because he was kind of on a perpetual ego trip (which is maybe par for the course when you’re emperor, no?), he gets painted with a broad brush as the beginning of the end.

Corruption, lust, tyranny— you name it, he did it, but it wasn’t enough to bring down the empire— not even close. And while the fact that the senate basically disowned him after he was deposed and scratched his name out of inscriptions and destroyed busts of him (more on that later), does indicate that he was unpopular, the next proper emperor after him did a lot to restore his reputation. I’m wary of the more outwardly negative accounts of Commodus because “I liked the old guy better,” is a very common refrain in history.

So remember how I said the empire got as big as it was going to get under Trajan? That’s pretty fucking big. In fact, it encapsulated much of what we would now call Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

So looking at this map now— let’s come to grips with something.

If your empire’s going to expand through military conquest, and you’re going to impose your gods on those people you just brutally conquered (okay, okay, in a lot of places Roman religion was practiced in combination with local religions, but still), impose your language on them (actually, let’s bring back Latin as the lingua franca! I’m dead serious— look we just did it when we said lingua franca), instate taxation and recruit labour (sometimes, mostly, enslaved) from conquered populations— then maybe you should expect some of these people from these far-flung places to come to Rome and vie for power. No taxation without representation, right?

And to that end, Rome was, by many accounts, a very cosmopolitan place. People from all over the empire came and lived together and while it’s arguable whether or not there was the same kind of pseudo-scientific racism that came out of British colonialism, it is patently evident that there was still lots and lots and lots of xenophobia. Put a pin in that.

So after Commodus is killed—a very scandalous affair involving conspiracy, lovers, beheading, strangling— there’s The Year of the Five Emperors, 193 CE where a bunch of people vied for power but ultimately, history goes to the victors so we don’t care about them, they’re wasting our time, we want to get right to the good part—

Septimius Severus — The first emperor of Rome to come from the continent of Africa, he was from a Libyan family. His ancestral home Leptis Magna (now Al-Khums) is an extremely well preserved ancient site and features many exciting examples of how Roman culture spread far and wide to the provinces, from big structures like columns and temples and basilicas, to the details on them like Medusa heads (an apotropaic (warding off evil) symbol also found on the aegis (shield) of Athena). He was by most accounts a pretty effective emperor and certainly cleaned up after Commodus, even while restoring his name and rehabilitating his reputation. Septimius was a military guy, but a political outsider. He wasn’t exactly currying much favour from the senate by favouring the equites (a class below the nobility, could be thought of like knights). He conquered (mostly Africa), he social welfared, he did all the right things. Despite not being “Italian,” he was hardly the first Emperor to be born elsewhere (my poor little meow meow, Emperor Claudius, was born in Gaul!), but it’s possible his Berber heritage caused a stir—

We can get an impression of the public perception of Septimius from the literary evidence of the time. The Roman poet Statius was Septimius’s contemporary and he wrote an ode to the emperor, in which he says, “Did your ancestral Leptis really bring you to life amid the far-distant Syrtes […] Your speech is not Punic, nor is your dress. Your mind is not that of a foreigner ? you are Italian, Italian!” Statius Silvae 4.5 (ll 29-30, 45-46).

This was an ode, definitionally in praise of Septimius, that was probably paid for by the Emperor himself through patronage. And even if he didn’t benefit monetarily, this poem certainly gave Statius lots of social clout in return, but this insistence that “his mind is not that of a foreigner,” that he’s just as good as an Italian, reeks a little of the kind of xenophobia that existed in Rome, and indicates that Septimius specifically was at least somewhat conscious about dispelling any aspersions that could be cast upon him because of his nationality.

To that end, I ultimately don’t think Septimius’s nationality factored in all that much to his time as emperor—but we should still be skeptical of how these potential xenophobic impressions of the Emperor would have affected the way he is depicted in historical sources, most of which were written many years after his reign by people with very little first-hand experience of it.

Citation:

Jerary, M. Tahar. “SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS THE ROMAN EMPEROR, 193-211 AD.” Africa: Rivista Trimestrale Di Studi e Documentazione Dell’Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente 63, no. 2 (2008): 173–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25734499.

8 ) Caracalla and Geta… the failsons of the hour.

So because of a lot of the baggage that came with Septimius Severus’s rule and the way Roman historiography gets nigh tropey about good fathers and bad sons— we have to note that the sources we have for Caracalla and Geta are deeply, deeply biased.

The xenophobia these sources might have expressed towards their father may not have directly carried over thanks to their full-blooded Roman mother Julia Domna. But still, they had a tough act to follow, and maybe weren’t the best people for the job.

Really the history of the Roman Empire could be told as one long cautionary tale against nepo babies.

A moment for those sources, that I’ve mostly only alluded to until now. For the second century CE, teetering into the third, we have a couple of heavy hitters in terms of actual Ancient Historians that were trying to record History.

Historia Augustae - authorship hotly contested and to this date definitively unknown, date of writing also dubious but most scholarly consensus would put it around the 4th-5th centuries CE. So okay, a history book written one hundred years after the events it is purporting to retell… alarm bells should be going off in your heads, people!

Cassius Dio - He lived in the 1st and 2nd century CE, so better— a contemporary! Ah… except, of the 80 books he wrote of Roman history from the literal founding of Rome to his present day… only the first 21 survived… and he doesn’t start talking about Septimius Severus and sons until books 75-80— which only exist in fragmentary form— or as summarized by other later authors. Not great!

Ammianus Marcellinus - writing in the late 300s, once again super far removed from the time he’s supposed to be writing about.

So just given that brief survey, we know we’re working with some rough sources. Despite that— what information can we actually gather about this fascinating family?

Caracalla, Geta and Damnatio Memoriae

Caracalla and Geta were not actually twins— I suspect they said in the movie for the Romulus and Remus implications, and indeed Paul Mescal even notes the famous statue on the gates on the way into Rome. Brother-killing is also kind of foundational to Rome’s mythology.

Still, in real life, Caracalla was older than Geta by a year, and he was even briefly co-emperor with his dad before Septimius died. After that, he got to be co-emperor with his little brother, but because they were brothers and humans are humans— they fought!

I thought in the movie, Joseph Quinn’s Geta was much more like the impression of Caracalla we get from history— large and in charge, but I can see why flipping the dynamic maybe made the fact that Geta dies first a little more dramatic.

Speaking of Geta dying— yeah! He is very famously is killed by Caracalla— maybe not as directly as seen in the movie— historical accounts say he made some of his Praetorian guards do it.

But as if killing Geta wasn’t enough— Caracalla wanted to kill even the thought of him. He wanted to erase him from history and to do so, he carried out a policy of Damnatio Memoriae, which translates literally to damnation of memory.

This was a fairly common practice when political tides would turn and there was a dead person to scapegoat. And obviously it wasn’t 100% foolproof or effective or we wouldn’t be talking about Geta today!

It is a pretty self-explanatory phenomenon: destroy the many, many artefacts and physical manifestations of glory that it is customary for emperors/men in power in Ancient Rome to create and in doing so, rob these men, who we now deem to be terrible, of the main thing their power-grabbing was in service of— Kleos, glory, immortality through memory.

This is a picture called the Severan Tondo— a tempera panel painting on a round piece of wood— It’s a family portrait of Septimius Severus, his wife Julia Domna, and their sons… Caracalla and… ?

Geta’s face is rubbed out of this family portrait, as well as others, and many busts and statues of him are destroyed.

This image is often used as a representation of the whole phenomenon of Damnatio Memoriae because it kind of punches you in the face with the reality of it— like we’re not even allowed to remember Geta as a kid with his family— he’s gone! He’s erased from time!

I liked that the movie had another way of showing the theme of Damnatio Memoriae, because Geta’s death is more of a big climactic moment— the subtler aspects of damnatio memoriae were shown in things like the way they scratched out Russel Crowe Gladiator’s name on the victors list inscription and had to hide his armor away in a secret hidden tomb.

The theme of Damnatio Memoriae is actually cleverly peppered throughout the film— there’s a part when Joseph Quinn, after discovering the plot to overthrow him, yells at Acasius and Lucilla that “history will forget your name” 🚨 🚨 🚨 FORESHADOWING 🚨 🚨 🚨

I also thought way Macrinus unceremoniously deposits Joseph Quinn’s decapitated head on a plinth could represent how busts of Geta were eventually destroyed— especially because there’s that whole moment where they facetuned a bust of Marcus Aurelius to look just like Paul Mescal (I mean this is just conjecture, Paul Mescal does have a very Aquiline nose so maybe the resemblance was already there).

I found the depiction of Caracalla as infantile and hapless to be an…. interesting choice. If ancient busts are to be believed— he was a little more butch in his presentation than Fred Hechinger’s interpretation, but I think both are valid.

What I find troubling is that Caracalla didn’t die that soon? He was actually sole Emperor for like six years (211-217 CE), and though he allegedly made his mom do all his administrative tasks because he found them boring (maybe learned helplessness is not exactly a modern phenomenon…), he still built a huge baths complex, had a few domestic policies, and tried to start war with Parthia, which was unsuccessful and he died while trying. Sad, but still not quite the indignity of getting a nail in the ear during your first gladiator games as solo emperor— and then being promptly usurped!

Macrinus was actually a real person, and did usurp Caracalla— though he was certainly not as swaggatrocious (new term I just coined: adj. evil in an extremely fun way) as Denzel Washington played him, and he also did ascend briefly to being an Emperor. He may have even orchestrated the death of Caracalla, but in a much more boring way.

With all that said— if Rome was actually at the precipice of falling at the time of Caracalla and Geta, it would be at least in part due to the unchecked and brutal expansion of the empire and the rotting bureaucracy in Rome that could barely keep up with it— not like just one guy being kind of terrible. Or even two guys being terrible.

The Roman Emperor is basically always terrible, but okay it’s possible that some were worse than others, and in Roman historiography it’s really easy and neat and fun to blame all of the ills of society on one guy. To be fair to the historiographers, the Roman empire kind of asked for it by making one guy be the figurehead. At least when it was an oligarchy in the Republic, there were a few different guys to blame. Or groups of guys. Little cliques of guys. Now we only get one guy?

The over-exaggerated reputation of goodness as some particular quality of emperors among Julio Claudians/Nerva-Antonines I think comes from this easy narrative the attitude generates— the association of these first few emperors as “founding father”-types for the empire, gives us clean lines where we can divide different phases of the empire’s success. We can attribute the qualities of the massive and multifarious collection of people under the same political aegis to the qualities of the self-imposed figurehead of that collective— and though that can lead to compelling historical narratives— these narratives are often a skewed or incomplete image of the past.

Of course, a movie can’t go into the fraught authorship of the Historia Augustae. And I don’t even think that the American or, technically in Scott’s case, British-filtered-through-Hollywood perspective on Rome is a bad thing. It’s reception! Of course this movie is speaking to its contemporary audience, not in the boring, complicated language of historical scholarship, through symbols and stories and arcs that they can appreciate and connect to their own lives. That’s what makes an effective story— the ability to draw that empathy out of the audience.

These anchor points of familiarity— yes, even the graffiti and inscriptions in English— trigger subliminal cues in our brains — and it’s how directors skillfully use the language of cinema to achieve good storytelling.

AND SO ULTIMATELY, IT’S ALL FINE!

I personally would love to live in the world of this alternate history of Rome where somehow the lost grandson of Marcus Aurelius returned and fixed despotism by shouting why can’t everyone just get along! Sure we lose our proto-genderqueer emperor Elegabalus and even worse, that great Lawrence Alma-Tadema painting The Roses of Heliogabalus. But maybe in this world, the Library of Alexandria never burned down or Ronald Regan was never president. That’s the thing about art— it makes you think!

I’ll end on that happy thought.

If you’ve read this far, you can have 0.4% of my Classics degree, or at this point— get your own.

Citations and further reading:

Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars

Roger Kean - A New History of the Roman Emperors (2009)

Fun fact, this is the book Mary Beard wrote after the class I took with her on Suetonius: https://wwnorton.com/books/9780871404220

Reading List for the Severan Dynasty (which, transparently, I got off of Reddit but then cross referenced with what I know, these are mostly good sources!):

Clifford Ando - Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: A critical century

Anthony R. Birley - Septimius Severus: The African emperor

Michael Sage - Septimius Severus and the Roman Army

Illka Syvänne - Caracalla: A millitary biography

Alex Imrie - The Antonine Constitution: An Edict for the Caracallan Empire

Martijn Icks - The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome's Decadent Boy Emperor

John S. McHugh - Emperor Alexander Severus: Rome's age of insurrection, AD 222-235

Michael Grant - The Severans: The Changed Roman Empire